The Villagers Don't Want War. The Parasitic Class Profits from War. The Villagers Versus The Parasites.

content aggregator | Ben Norton and Katrina vanden Heuvel

The US military launched 469 foreign interventions since 1798, including 251 since the end of the first cold war in 1991, according to official Congressional Research Service data.

The United States launched at least 251 military interventions between 1991 and 2022.

This is according to a report by the Congressional Research Service, a US government institution that compiles information on behalf of Congress.

The report documented another 218 US military interventions from 1798 to 1990.

That makes for a total of 469 US military interventions since 1798 that have been acknowledged by the Congress.

This data was published on March 8, 2022 by the Congressional Research Service (CRS), in a document titled “Instances of Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad, 1798-2022.”

The list of countries targeted by the US military includes the vast majority of the nations on Earth, including almost every single country in Latin America and the Caribbean and most of the African continent.

From the beginning of 1991 to the beginning of 2004, the US military launched 100 interventions, according to CRS.

That number grew to 200 military interventions between 1991 and 2018.

The report shows that, since the end of the first cold war in 1991, at the moment of US unipolar hegemony, the number of Washington’s military interventions abroad substantially increased.

Of the total 469 documented foreign military interventions, the Congressional Research Service noted that the US government only formally declared war 11 times, in just five separate wars.

The data exclude the independence war between US settlers and the British empire, any military deployments from 1776 to 1798, and the US Civil War.

It is important to stress that all of these numbers are conservative estimates, because they do not include US special operations, covert actions, or domestic deployments.

The CRS report clarified:

The report likewise excludes the deployment of the US military forces against Indigenous peoples, when they were systematically ethnically cleansed in the violent process of westward settler-colonial expansion.

CRS acknowledged that it left out the “continual use of U.S. military units in the exploration, settlement, and pacification of the western part of the United States.”

The Military Intervention Project at Tufts University’s Center for Strategic Studies has documented even more foreign meddling.

“The US has undertaken over 500 international military interventions since 1776, with nearly 60% undertaken between 1950 and 2017,” the project wrote. “What’s more, over one-third of these missions occurred after 1999.”

The Military Intervention Project added: “With the end of the Cold War era, we would expect the US to decrease its military interventions abroad, assuming lower threats and interests at stake. But these patterns reveal the opposite – the US has increased its military involvements abroad.”

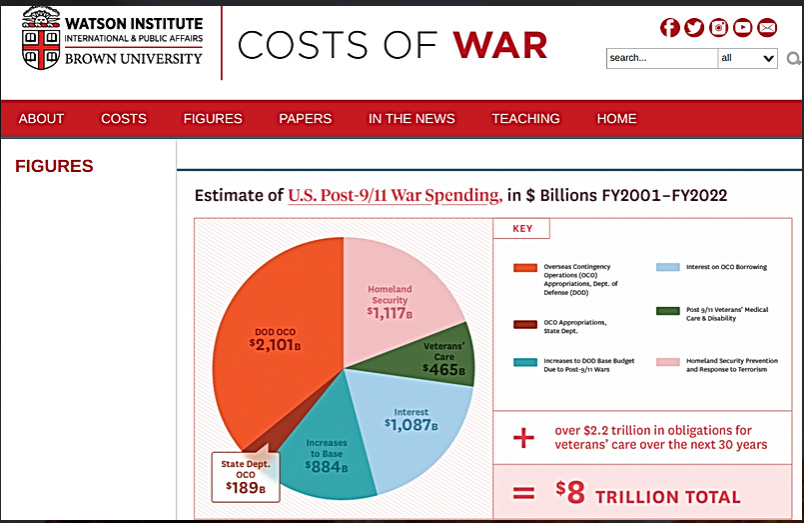

According to the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University, the United States has spent $2.313 trillion on the war in Afghanistan since 2001.

The Watson Institute is a nonpartisan research project that seeks to document the direct and indirect human and financial costs of U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and related counterterrorism efforts. The project is the most extensive and comprehensive public accounting of the cost of post-September 11th U.S. military operations compiled to date.

The Watson Institute's estimate of the cost of the war in Afghanistan includes the following:

Direct military spending, such as the cost of troop deployments, equipment, and operations

Reconstruction and development assistance

Veterans' care and disability payments

Interest on money borrowed to finance the war

The Watson Institute's estimate does not include the indirect costs of the war, such as the loss of economic opportunity and the impact on human health and well-being.

The war in Afghanistan has been the longest war in U.S. history. It has also been one of the most expensive. The Watson Institute's estimate of the cost of the war is a stark reminder of the high price that the United States has paid for its military intervention in Afghanistan.

source - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Costs_of_War_Project

Printing money to fund wars.

Thanks to Biden, the War Party is back

The president's policies reflect his appointments: ideologues who should have retired after previous foreign policy debacles.

SEP 05, 2023

President Joe Biden recently appointed Victoria Nuland, Dick Cheney’s point person on Iraq, acting deputy secretary of State, the department’s number two official. He named Elliott Abrams, convicted perjurer and grim apologist for Central American torturers under Ronald Reagan, to his Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy.

Meanwhile, Bill Kristol, perfervid lobbyist for the Iraq War, cadged $2 million to pay for TV ads urging Republicans to stay the course in Ukraine. War may or may not be the health of the state, but surely it is a tonic for neo-conservative armchair warriors.

In the White House, while Biden has touted a new “foreign policy for the middle class,” his policies have largely been a reversion to the ruinous policies of the foreign policy establishment and its belief in America’s benevolent hegemony.

Once more America is described as the indispensable nation. Once more officials preach about a “rules-based order” that they invoke and violate at will. Once more we’re summoned to a global struggle between democracy and authoritarianism. We’re waging a proxy war with Russia in Ukraine while simultaneously gearing up for a Cold War with China, imposing economic sanctions on 26 countries, maintaining over 750 bases in 80 countries, and dispatching forces to over 100 countries and across the seven seas.

While Biden has rejoined the Paris Climate Accords, his climate czar, John Kerry, has virtually disappeared amid the geopolitical fixations. Biden’s turn from Trump’s heresies was largely to reassert the old (and discredited) establishment gospel.

His appointments reflect the policy. The leaders of his foreign policy team — Secretary of State Antony Blinken and national security advisor Jake Sullivan — are veterans implicated in the failures of the past. The hawkish Blinken was an ardent champion of the Iraq War, surely the most disastrous adventure since Vietnam. Sullivan, Hillary Clinton’s favorite strategist, was instrumental in the Libyan debacle, which he exuberantly framed as an example of the “Clinton doctrine’ before it left Libya in violent chaos. And now, even the most rabid neocons are back in the saddle.

After the Iraq debacle, one would have thought these ideologues had, in James Fallows’ words, “earned the right not to be listened to.” They would be retired in disgrace, left to write their memoirs and apologias in deserved obscurity. Two phenomena enabled their return to establishment graces. The first, of course, was Trump — and the accompanying Trump derangement syndrome. The neo-conservatives in particular were welcomed back into the establishment embrace when, with few exceptions, such as Abrams who served as Trump’s point in the madcap effort to bring down the Venezuelan government, they broke with Trump and issued furious denunciations of his “isolationist” America first rhetoric.

The second salve for their fortunes was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. All of their Cold War tropes were given new life: Putin was evil; if not stopped in Ukraine, he would move on to Poland or the Baltics; only military defeat could deter him. American responsibility for the events that led up to the war — the extension of NATO to Russia’s borders, the scornful dismissal of Russian warnings (across the political spectrum) against including Ukraine in the bloc, the meddling in Ukrainian politics (most notably by the egregious Nuland) — was immediately forgotten or dismissed as irrelevant.

The perils of this resuscitation of the U.S. war party are apparent in Ukraine. Neo-conservatives like Max Boot and Eliot Cohen now assail the administration for its caution in arming the Ukrainians, arguing that Putin’s red lines can be safely ignored and that we should supply Ukraine with the arms needed to bomb Russia and Crimea directly. Russia must be not merely defeated but routed.

As Cohen put it in the Atlantic, “we need to see masses of Russians fleeing, deserting, shooting their officers, taken captive, or dead. The Russian defeat must be an unmistakably big, bloody shambles.”

As the Ukraine war has fallen into a brutal and bloody stalemate, the administration has slowly acceded to the calls for escalation — sending tanks, then cluster bombs, then approving F-16s via allies, with longer range missiles soon to follow. It is a course that bets much on the restraint of a leader we’re told is a madman.

The broader implications are even more ominous. Biden has revived the rhetoric and the ambitions of American exceptionalism. The U.S. will sit at the head of every table; we will define the rules — and police them across the world.

As Robert Kagan, Nuland’s husband and leading neo-conservative pundit, puts it, “Superpowers don’t get to retire.” Kagan asserts baldly what this crew believes: “The time has come to tell Americans that there is no escape from global responsibility…the task of maintaining a world order is unending and fraught with costs but preferable to the alternative.”

In reality, the time has come for a brutally honest assessment of the growing costs and increasing perils that come from the militarization of our foreign policy and the relentless effort to police the world. As the Quincy Institute’s Andrew Bachevich puts it, “Our actual predicament derives from the less than honest claim that history obliges the United States to pursue a policy of militarized hegemony until the end of time. Alternatives do exist.”

Unfortunately the Biden administration appears committed to the war party’s failed playbook of the past, and the rising costs of a global policy we neither need nor can afford.

Katrina vanden Heuvel is editorial director and publisher of The Nation. She served as editor of the magazine from 1995 to 2019. She writes a weekly column for The Washington Post and is President of the American Committee for U.S.-Russia Accord.